Subliminal Overtones: The Caves

Finding the Hidden Notes Between the Notes

“There are these places in between, which I call caves.”, Nigel Tufnel, Guitar World 2009

In the world of guitar lore, inspiration sometimes arrives from the most unexpected sources, even a fictional rock legend.

In the world of guitar lore, inspiration sometimes arrives from the most unexpected sources, even a fictional rock legend.

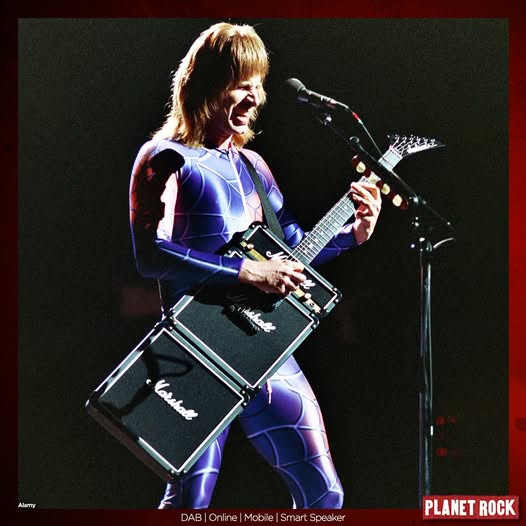

Nigel Tufnel, the lead guitarist of the parody band Spinal Tap (portrayed by Christopher Guest in the 1984 mockumentary This Is Spinal Tap), once introduced a curious idea he called caves.

In a 2009 Guitar World interview promoting Spinal Tap’s reunion album Back from the Dead, Tufnel described these caves as “little hidden places between notes that most players overlook.”

Although offered jokingly, the concept captures a real musical truth: between the fixed pitches of the Western chromatic scale, there exists an infinite landscape of subtle sounds and overtones.

Exploring those spaces can create the illusion of being somewhere else musically, a sensation that feels fresh even on a well-worn fretboard.

What Are “Caves” in Guitar Playing?

Western music divides an octave into 12 equal semitones, A to G♯/A♭.

But as Tufnel whimsically points out, there are “places in between.”

Between C and D, or between a note and its sharp or flat, lies a tiny region of pitch that our fretted guitars normally skip over.

When you bend a string or slide your finger slightly off-center, you can momentarily enter that micro-space, hearing faint resonances that don’t belong strictly to either note.

Tufnel’s playful caves correspond to what musicians and acousticians call microtones, pitches that fall between the standard semitones.

For instance, a quarter-tone sits halfway between two adjacent notes. Traditional guitars aren’t built for this nuance, but bending, sliding, or using feedback lets players access those hidden frequencies.

As Tufnel quipped, “If you flat the third then you’ve got a minor. Big deal, right?”

His point, delivered in classic Spinal Tap fashion, was that real creativity may lie not in naming scales but in hearing what’s between them.

The Illusion of Hidden Notes

When you linger in one of these in-between zones, your ear often perceives the echoes of the neighboring pitches.

Tufnel explained that you might “hear the echo of the B and the B♭, but it’s not quite the same,” creating an illusion of being somewhere outside normal tonality.

Technically, this illusion arises because our ears interpret overtones and tiny pitch shifts as beating or shimmer.

Slightly detuned frequencies interact, producing ghostlike resonances that seem to float between the notes. Guitarists experience this naturally when using feedback, harmonics, or expressive bends that stop just short of a defined pitch.

“Going Caver”: Playing Between the Frets

Tufnel joked that when he ventured into those uncharted tones he would announce, “I’m goin’ caver on ya.”

It’s a tongue-in-cheek way of saying he’s playing between the frets to summon strange overtones.

There’s no verified record of specific Spinal Tap songs using this technique in a deliberate, technical sense, after all, the band and its guitarist are part of a satire, but the idea serves as a metaphor for musical exploration.

A good musician can go caver anytime by intentionally leaving the safety of the grid and searching for expressive imperfections.

How to Explore “Caves” on Your Guitar

Even though our instruments are fretted for fixed pitches, there are several ways to explore the territory between notes:

- Micro Bends and Slides: Bend a note slightly less than a semitone, just enough to land between two pitches. Blues players do this constantly when hovering between the minor and major third. These bends imitate the fluid intonation of the human voice and reveal those sweet microtonal colors.

- Vibrato Shading: A slow, wide vibrato makes the pitch oscillate around the main note, brushing against microtones above and below. This motion can produce subtle beating between frequencies, enriching the overtone spectrum.

- Slide or Fretless Guitar: Using a slide (bottleneck) or a fretless neck lets you glide freely across the continuum of pitch. Holding a sustained tone between C and C♯ often reveals shimmering overtones and a sense of tension that can sound haunting or exotic.

- Harmonics and Resonance Experiments: Lightly touch open strings at unusual points and listen for faint, off-center harmonics. Some natural harmonics fall slightly flat or sharp relative to equal temperament, placing them right inside those caves. Adding a bit of reverb or delay can emphasize their ghostly quality.

Why Piano Players Can’t Find Caves

Unlike guitarists, pianists are locked into the tempered grid. Every piano key is tuned to one of the 12 fixed notes per octave, leaving no room for microtonal exploration.

Once a key is struck, its pitch is determined entirely by the string’s preset tension, there’s no bending, sliding, or shading in between.

That’s why the expressive techniques guitarists take for granted, a quarter-tone bend, a slow vibrato, a subtle detune, simply don’t exist on the piano.

For all its harmonic richness, the piano lives inside the walls of the musical “cave,” while the guitar can wander freely through its tunnels.

Trust Your Ears

As you try these techniques, rely on your ears more than theory.

Every guitar and setup resonates differently; when you find a point where the tone suddenly blooms or produces a strange ring, you’ve likely discovered one of Tufnel’s hidden places.

Sound Over Theory: The Philosophy Behind the Joke

What makes the caves idea memorable is its reminder to value sound itself over rigid theory.

Tufnel’s parody of guitar-hero ego ironically hides a genuine artistic lesson: theory explains, but listening reveals.

Music doesn’t always need labels.

If bending a note slightly sharp, or letting an overtone ring oddly, moves the listener, that’s the only justification it needs.

Used tastefully, these microtonal shadings add emotion and mystery, the musical equivalent of light filtering through cracks in stone.

Embrace the “Caves” in Your Playing

Whether you take Nigel Tufnel’s words as parody, poetry, or both, the idea of searching for hidden notes between the notes is inspiring.

It urges guitarists to slow down, listen more closely, and explore the liminal spaces their instruments allow.

Next time you’re improvising, try to go caver for a moment, bend a note to an unfamiliar place, or let a strange harmonic linger.

Even within the frets of a standard guitar lies a vast network of secret chambers of sound.

As Tufnel might say, that’s one louder than ordinary music.